When we first started the transition from actual horses to horsepower, to say the roads were chaotic would be an understatement. Drivers didn’t need a license, lane lines didn’t exist, and the lack of traffic signs made four-way stops a recipe for disaster. The first official stop sign appeared in Detroit in 1915. Small, white, and square, it seemed more like a request than a law. In 1923, the Mississippi highway department suggested that there be some sort of code in street signage—the more sides on a sign, the more dangerous the upcoming hazard. Circles designated the most risky stretch of road, as they were considered to have infinite sides. The octagon came in second and pointed out dangerous intersections, traditionally the four-way stop. They appear to have broken the side-counting strategy with diamonds and rectangles—the latter was for informational signage, while the former designated a moderately tricky stretch. Now go for a nice Sunday drive and remember your geometry!

Sure, “black” would be a fair response, but the term “black light” is an oxymoron because truly black light is impossible. Black light is actually from the slow lane of the spectrum—long-wave ultraviolet (UV-A) light. It’s the kind of light that makes your teeth and white t-shirt appear to glow, can reveal a counterfeit $50, and makes certain heavy metal posters obtainable from carnivals totally rad. But among the many amazing functions of black light, the most remarkable are found among insects and arachnids: certain scorpions fluoresce blue-green under black light, bees’ sophisticated eyes allow them to see a wide color spectrum that includes ultraviolet, and butterflies perceive gender differences (invisible to humans) through ultraviolet light to help them find a date. But unfortunately for moths and other flying insects, black light is also used as a lure in electric “bug zappers,” so it could well be the last thing they see on a summer night.

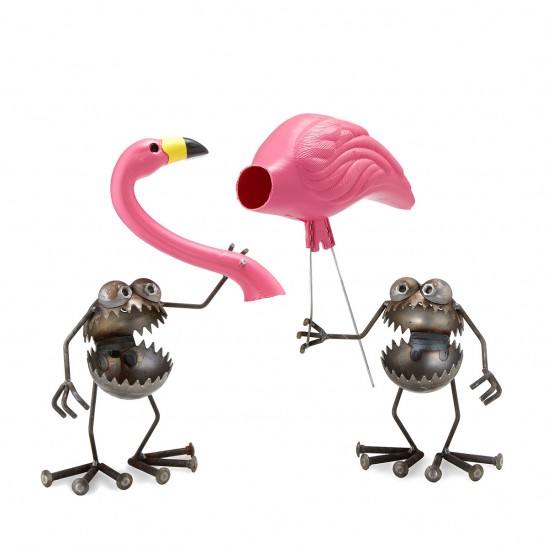

We’ve all heard that you are what you eat, but flamingos are the poster birds for this aphorism. They’re best known for their bright pink plumage, but did you know that this color comes from their diet? Flamingos are born with white feathers, but they obtain a pink cast through eating brine shrimp, which contain generous amounts of beta-carotene. This same compound is found in carrots and is essential to vitamin A production for birds and humans alike. So, healthy flamingos in the wild are naturally a vivid pink-orange color, but their captive colleagues are kept in the pink with beta-carotene supplements. The plastic flamingos that live on lawns, however, get their color from industrial red dyes and do not need to be fed.

Nope. But if they had opposable thumbs, they would certainly be inclined to dust off the old embroidery thread. Studies have shown that cows form close bonds with others in their herd, displaying reductions in stress when they’re paired with their besties, as opposed to some random cow from down the meadow. These best friends tend to spend most of their time together, enjoying the leisurely pleasures of an afternoon on the farm as a platonic twosome. Dairy farmers are now starting to appreciate this udderly adorable friendship fact, as a happy cow produces more milk. Slumber party in the barnyard!

It certainly does beat the odds. It’s estimated that only one out of 10,000 people will be struck by lightning in their lifetime—although this is still more likely than winning millions in the lottery, which has odds in the neighborhood of 1 in 259 million. But one man named Roy Sullivan laid claim to the unluckiest luck in the world by being struck by lightning seven times. This was partly due to the fact that he worked a ranger in Shenandoah National Park and was exposed to a lot more storms than average. But it got to the point where Sullivan began to claim that clouds were actually following him. He started carrying a bucket of water with him whenever there was a storm, which came in handy several times because the lightning had a tendency to set his hair on fire. The chances of an ordinary person being struck by lightning seven times are somewhere around 1 in 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. Lucky guy! (And he almost got even luckier: once he was helping his wife hang laundry out to dry, and she was struck by lightning instead of him!)

If by unicorns, you mean majestic marine life with a unicorn-like horn, then yes! They do! Though the existence of the narwhal might not be uncommon knowledge to all, a quick office poll is all you need to realize that not everyone has been clued in to this myth-worthy creature. The narwhal is an arctic whale with what looks like a tusk. In medieval times, this tusk was given to royalty and passed off as a unicorn horn. However, that tusk is actually a small town dentist’s dream—it’s technically a tooth that grows in a counterclockwise spiral for up to ten feet. Try fitting that with a retainer.

That oh-so-stylish, late-Sunday-morning institution is not some natural expression of human need that evolved over the centuries like, say, dinner. It was the brainchild of an Englishman named Guy Beringer. As described in his 1895 treatise “Brunch: A Plea,” Beringer felt that brunch would help resolve the conflict between two age-old enemies: hangovers and the English breakfast. In England at the time, a typical breakfast menu included fried bacon, fried mushrooms, fried sausages, fried potatoes, fried oatcakes, along with the occasional meat pie or black pudding, just to round things out. All of this could land pretty hard on a stomach soured by last night’s revels. The solution Beringer proposed was a hybrid meal, where you could start with lighter, lunch-time fare before gradually working your way to heartier food as your body returns to normal. And of course, some hair-of-the-dog-that-bit-you would have some medicinal value, as well. In spite of the fact that Beringer’s article may have been intended as a joke, seeing as how it was published in the satirical magazine Punch and was addressed to the needs of “Saturday-night carousers”, it didn’t take long for people to see the genius in his idea, making brunch the best thing to happen in the morning since sleeping in late.

Among his many epigrams, Arts & Crafts guru Elbert Hubbard declared, “boredom is a matter of choice, not circumstance.” It seems that the Boring Institute couldn’t agree more, designating July as “National Anti-Boredom Month.” Writer Alan Caruba founded the Institute in 1984 as a media spoof of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade; his mock press release claimed that they were running ten-year-old footage of the parade on TV to explain what he saw as an exceedingly boring and repetitive annual event. Despite its Thanksgiving associations, the Boring Institute’s month of Anti-boredom events and observations serves as an antidote to the summertime blues—when many kids, free from the structure of the school year, try their caregivers’ patience and creativity with cries of “there’s nothing to do!” Since its satirical beginnings, the Boring Institute has shifted focus to issues of “self-awareness” to combat depression and related self-destructive behaviors. So, for Caruba, boredom can be a serious business, but fighting boredom for families over the summer relies on the thoughtful cultivation of a fun, anti-boredom mission.

Among his many epigrams, Arts & Crafts guru Elbert Hubbard declared, “boredom is a matter of choice, not circumstance.” It seems that the Boring Institute couldn’t agree more, designating July as “National Anti-Boredom Month.” Writer Alan Caruba founded the Institute in 1984 as a media spoof of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade; his mock press release claimed that they were running ten-year-old footage of the parade on TV to explain what he saw as an exceedingly boring and repetitive annual event. Despite its Thanksgiving associations, the Boring Institute’s month of Anti-boredom events and observations serves as an antidote to the summertime blues—when many kids, free from the structure of the school year, try their caregivers’ patience and creativity with cries of “there’s nothing to do!” Since its satirical beginnings, the Boring Institute has shifted focus to issues of “self-awareness” to combat depression and related self-destructive behaviors. So, for Caruba, boredom can be a serious business, but fighting boredom for families over the summer relies on the thoughtful cultivation of a fun, anti-boredom mission.