When you hear the word foolscap, maybe the image that pops into mind is an old-time schoolhouse with an unruly student seated in the corner wearing the pointed cap of shame. That kind of cone-shaped hat did exist, but it was called a dunce cap. A fool, on the other hand, was what we would now think of as a court jester, and their associated hat was of the variety that would curl up and out into several points, perhaps with a jingling bell attached to the tip of each. The fool and his coxcomb were such an iconic image that, starting as early as the 1500s, they were even used as the watermark to indicate a particular size of paper. So while fool’s cap is worn by a fool, foolscap—as a single world—is a size of paper, and is unlikely to be worn by anyone.

When you hear the word foolscap, maybe the image that pops into mind is an old-time schoolhouse with an unruly student seated in the corner wearing the pointed cap of shame. That kind of cone-shaped hat did exist, but it was called a dunce cap. A fool, on the other hand, was what we would now think of as a court jester, and their associated hat was of the variety that would curl up and out into several points, perhaps with a jingling bell attached to the tip of each. The fool and his coxcomb were such an iconic image that, starting as early as the 1500s, they were even used as the watermark to indicate a particular size of paper. So while fool’s cap is worn by a fool, foolscap—as a single world—is a size of paper, and is unlikely to be worn by anyone.

Uncommon Knowledge: What’s the best way to rate an ultimate champion?

December 8, 2013 Is it brains or brawn? If you’re one of the well-rounded individuals to compete in Chess Boxing, you know it’s a fast-paced mix of both. First notably appearing in a French comic book in 1992, the hybrid sport has leapt from the page to the ring, with growing followings in Berlin and London. Participants must be skilled boxers and at least Class A-strength chess players, as a full match consists of eleven four-minute rounds: six of chess and five of boxing. Talk about an intense check mate.

Is it brains or brawn? If you’re one of the well-rounded individuals to compete in Chess Boxing, you know it’s a fast-paced mix of both. First notably appearing in a French comic book in 1992, the hybrid sport has leapt from the page to the ring, with growing followings in Berlin and London. Participants must be skilled boxers and at least Class A-strength chess players, as a full match consists of eleven four-minute rounds: six of chess and five of boxing. Talk about an intense check mate.

It’s a sweetly eccentric holiday tradition: on Christmas morning the children rush to the Christmas tree, trying to spot a glass ornament shaped like a pickle. The lucky child who does so first is blessed with a year of good luck, or perhaps even an extra present. In America, the tradition first appeared during the 1890s when beautiful, glass Christmas ornaments began to be important from Germany. It was said that the holiday cuke was an old German custom, known as the Weihnachtsgurke. However, there is no historic evidence of such a tradition actually being practiced overseas. It appears that, instead, the Christmas pickle was part of a great American tradition: marketing. The story of the pickle’s German origins was most likely made up at that time to help sell more of the unusual ornaments, but the century of fun that it has inspired is completely authentic.

It’s a sweetly eccentric holiday tradition: on Christmas morning the children rush to the Christmas tree, trying to spot a glass ornament shaped like a pickle. The lucky child who does so first is blessed with a year of good luck, or perhaps even an extra present. In America, the tradition first appeared during the 1890s when beautiful, glass Christmas ornaments began to be important from Germany. It was said that the holiday cuke was an old German custom, known as the Weihnachtsgurke. However, there is no historic evidence of such a tradition actually being practiced overseas. It appears that, instead, the Christmas pickle was part of a great American tradition: marketing. The story of the pickle’s German origins was most likely made up at that time to help sell more of the unusual ornaments, but the century of fun that it has inspired is completely authentic.

A claqueur is a professional applauder. That’s right. They earned a living by attending operas, plays and ballets and clapping loudly. The position has appeared throughout history in some form wherever there were people whose large egos needed massaging, but it began to be formalized into an actual career in France during the Renaissance. By the 1800s, there were even professional organizations for them, and specialized skills: there were those hired to weep at tragedies, others who would laugh infectiously during comedies, and some guaranteed to cry out for encores. They could even extort money from popular performers with the threat of booing during their bows. So, who needs a claqueur today? Everyone! Imagine how much better life would be with someone guaranteed to find your jokes hilarious and your stories fascinating.

A claqueur is a professional applauder. That’s right. They earned a living by attending operas, plays and ballets and clapping loudly. The position has appeared throughout history in some form wherever there were people whose large egos needed massaging, but it began to be formalized into an actual career in France during the Renaissance. By the 1800s, there were even professional organizations for them, and specialized skills: there were those hired to weep at tragedies, others who would laugh infectiously during comedies, and some guaranteed to cry out for encores. They could even extort money from popular performers with the threat of booing during their bows. So, who needs a claqueur today? Everyone! Imagine how much better life would be with someone guaranteed to find your jokes hilarious and your stories fascinating.

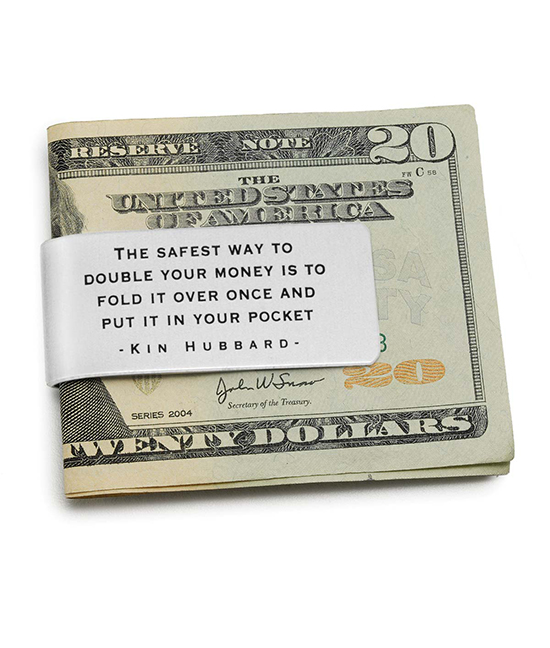

None. Zero. Nada. Not a single tree is cut down to make the great American greenback. It’s not because the government has instituted an environmentally responsible recycling program, but rather because the paper used for currency is completely unlike the stuff we use for printing and writing. Wood pulp-based paper is designed to be affordable and mass produced, but is not necessarily very durable. Paper money, on the other hand, needs to be able to survive years of wallets, pockets and vending machines. It also needs to be difficult to reproduce, as a way of deterring forgery. So those bills in your pocket are actually more like fabric, made from a unique, legally-protected blend of cotton and linen fiber.

None. Zero. Nada. Not a single tree is cut down to make the great American greenback. It’s not because the government has instituted an environmentally responsible recycling program, but rather because the paper used for currency is completely unlike the stuff we use for printing and writing. Wood pulp-based paper is designed to be affordable and mass produced, but is not necessarily very durable. Paper money, on the other hand, needs to be able to survive years of wallets, pockets and vending machines. It also needs to be difficult to reproduce, as a way of deterring forgery. So those bills in your pocket are actually more like fabric, made from a unique, legally-protected blend of cotton and linen fiber.

While no dinosaur is exactly dime-a-dozen these days, one might argue that the hardest to find is the Archaeopteryx. And not just any old proto-bird, but specifically the one known as the “Maxberg specimen.” It was dug from a German quarry in 1956. Eduard Opitsch, the quarry owner, allowed the Maxberg Museum to display the specimen while he sought a buyer for his find. But, although he received bids from various museums, in the end he simply decided to keep it himself. He took the fossil home, and it was never seen again. When Opitsch passed away in 1991, his home and records were examined with no luck—the Archaeopteryx had flown the coop for good.

While no dinosaur is exactly dime-a-dozen these days, one might argue that the hardest to find is the Archaeopteryx. And not just any old proto-bird, but specifically the one known as the “Maxberg specimen.” It was dug from a German quarry in 1956. Eduard Opitsch, the quarry owner, allowed the Maxberg Museum to display the specimen while he sought a buyer for his find. But, although he received bids from various museums, in the end he simply decided to keep it himself. He took the fossil home, and it was never seen again. When Opitsch passed away in 1991, his home and records were examined with no luck—the Archaeopteryx had flown the coop for good.

In 1877, a young man named Arthur Conan Doyle became a clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. One of his duties was to conduct intake interviews for new patients of pathologist Dr. Joseph Bell—who had a gift for deducing much of the same information simply by observing the details of a person’s dress and behavior. He was legendary for predicting a person’s birthplace, habits, recent actions and more without a word of explanation from the person. And while Dr. Bell was not Sherlock Holmes to the letter, he was periodically called in by the police to consult on criminal investigations, including the Jack the Ripper murders. Sometimes, however, life can also imitate fiction. In 1890—three years after Sherlock Holmes first appeared in prints—Dr. Bell went to assist on a particularly scandalous murder of a student by his tutor. Helping Dr. Bell was a ballistics expert who just happened to be named Dr. Watson.

In 1877, a young man named Arthur Conan Doyle became a clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. One of his duties was to conduct intake interviews for new patients of pathologist Dr. Joseph Bell—who had a gift for deducing much of the same information simply by observing the details of a person’s dress and behavior. He was legendary for predicting a person’s birthplace, habits, recent actions and more without a word of explanation from the person. And while Dr. Bell was not Sherlock Holmes to the letter, he was periodically called in by the police to consult on criminal investigations, including the Jack the Ripper murders. Sometimes, however, life can also imitate fiction. In 1890—three years after Sherlock Holmes first appeared in prints—Dr. Bell went to assist on a particularly scandalous murder of a student by his tutor. Helping Dr. Bell was a ballistics expert who just happened to be named Dr. Watson.

While this tabletop rule has been drilled into your head since you graduated from your high chair, its supposed origins suggest it’s more need-based than the pinnacle of politeness. During medieval times, everyone and their barber would be invited to elaborate dinners at long, crowded tables. With surface space at a premium, no elbow could be placed on the table without landing in someone else’s territory—or in their food! But seeing as how we now enjoy more spacious dining accommodations, have at it! Modern rules dictate that elbows are free game once you’ve put down your utensils.

While this tabletop rule has been drilled into your head since you graduated from your high chair, its supposed origins suggest it’s more need-based than the pinnacle of politeness. During medieval times, everyone and their barber would be invited to elaborate dinners at long, crowded tables. With surface space at a premium, no elbow could be placed on the table without landing in someone else’s territory—or in their food! But seeing as how we now enjoy more spacious dining accommodations, have at it! Modern rules dictate that elbows are free game once you’ve put down your utensils.