If you were a lady living in Victorian-era France, North America, or the U.K. and your favorite color was green, yep. For years, women flocked to a lovely emerald green hue used in fabrics and floral headdresses. Super flattering, right? Unfortunately for them (and the factory workers who made them and the fellow party guests the green-loving ladies interacted with), that brilliant hue was achieved by combining copper and arsenic. A group of society women found out about this somewhat inconvenient and dangerous fact and promptly blew the whistle, calling for a study and expose on the deadly duds. An expert concluded that a standard floral headdress contained enough arsenic to poison 20 people, while the green tarlatan used in ball gowns contained as much as half its weight in arsenic. What’s more, at least 60 grains would powder off during the course of an evening—with a lethal dose being just four or five grains for the average adult. Needless to say, this practice ended and we all went back to wearing clothing that wasn’t lethal. However, many fashion historians hypothesize that some of the older haute couture houses held on to a superstition against the bright, formerly dangerous hues, sticking with the more neutral blacks and whites that are still considered the height of chic today.

If you were a lady living in Victorian-era France, North America, or the U.K. and your favorite color was green, yep. For years, women flocked to a lovely emerald green hue used in fabrics and floral headdresses. Super flattering, right? Unfortunately for them (and the factory workers who made them and the fellow party guests the green-loving ladies interacted with), that brilliant hue was achieved by combining copper and arsenic. A group of society women found out about this somewhat inconvenient and dangerous fact and promptly blew the whistle, calling for a study and expose on the deadly duds. An expert concluded that a standard floral headdress contained enough arsenic to poison 20 people, while the green tarlatan used in ball gowns contained as much as half its weight in arsenic. What’s more, at least 60 grains would powder off during the course of an evening—with a lethal dose being just four or five grains for the average adult. Needless to say, this practice ended and we all went back to wearing clothing that wasn’t lethal. However, many fashion historians hypothesize that some of the older haute couture houses held on to a superstition against the bright, formerly dangerous hues, sticking with the more neutral blacks and whites that are still considered the height of chic today.

There’s no shame in a re-gift. Sometimes a sweater from your knitting-obsessed Aunt Laura just doesn’t highlight your eyes, and there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s easy to re-wrap a candle with a scent you don’t like or return a set of socks that don’t quite fit—but what do you do with a 1250-pound, nine-foot cheddar wheel? That was the conundrum Queen Victoria faced at her 1840 wedding to Prince Albert. The cheesy gift was produced by a cooperative of cheese makers from two villages, meaning two entire villages of cheese folk felt that this would be an excellent gift for a newly married set of cousins (yep). Needless to say, Queen Victoria definitely didn’t register for this gigantic wheel of cheese and decided to send it on a tour of England instead. After its journey, however, the cheese never made it back to its rightful owner, as Queen Victoria refused to take it back. If that doesn’t make the case for gift receipts, we don’t know what does.

Mariner Cheese Board | $32

Uncommon Knowledge: What Does “Mary Had a Little Lamb” Have to do with Thanksgiving?

November 22, 2015

Oh, only EVERYTHING. As you enjoy your beautiful table spread, togetherness, and that fourth slice of pie, maybe give a little nod to Mary, her lamb, and Sarah Joespha Hale, the writer of the nursery rhyme. Hale campaigned for 20 years and through five presidents to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She lobbied congressmen, wrote annual editorials, and sent letters to every governor in the United States. Sadly, no president or elected official listened to her until Abraham Lincoln. She convinced Lincoln in a letter dated September 28th, 1863 that Thanksgiving would be a great way to unify the country after the Civil War ended. Lincoln agreed and declared the last Thursday in November as our country’s third national holiday, sharing company with Independence Day and Washington’s birthday. Congress officially set the date into U.S. law in 1941. So the next time you’re passing the stuffing, give thanks for Mary and her little lamb.

Sinclair the Sheep Rug | $98

You smell fresh popcorn, and somehow you’re transported back to that old movie house where you had your first date. Or you smell the signature odor of books, and you’re wandering the stacks of your hometown library in your mind…what is this wizardry? Oh, just your sense of smell tapping into the part of your brain responsible for memory and emotion. Our sense of smell is most closely tied to memory and emotion because the olfactory bulb—the organ that translates chemical content in the air to sensations of smell—has the most direct line to the amygdala and hippocampus, two parts of the brain that play a big role in processing memory and emotion. Our visual, auditory, and tactile senses don’t pass through these brain areas, so they don’t have such close ties to distant memories and powerful emotions. Evolutionarily speaking, the amygdala and hippocampus are primitive parts of the brain in that we share them with our earliest mammal ancestors. This helps explain why certain smells trigger powerful associations that you can’t quite put your finger on—they’re ancient associations with instinct as compelling as the call of the wild.

Longplayer, an epic musical composition and A.I. project initiated by Jem Finer (of Pogues fame) has been playing for less than two percent of its intended duration. Designed to last a millennium without repetition, Longplayer is barely getting warmed up as it approaches the fifteen-year mark of its sonic lifespan. To put that in perspective, the longest Pink Floyd track is about 25 minutes (“Shine On You Crazy Diamond”), and Wagner’s Ring cycle clocks in at over 16 hours. But these compositions are mere blips compared to Longplayer’s thousand-year run. If you spent your entire life listening to the meditative tones of Longplayer (and who has the time?), you couldn’t hope to hear more than ten percent of the evolving composition. But regardless of how long you can listen, the piece offers a sensory analog to the expansiveness of time and the difficulty that the human lifespan poses to our perception of much beyond “the now.” In an age of music by instant-gratification download, Longplayer serves as a contemplative antidote to the impatient listening encouraged by MP3s or streaming audio.

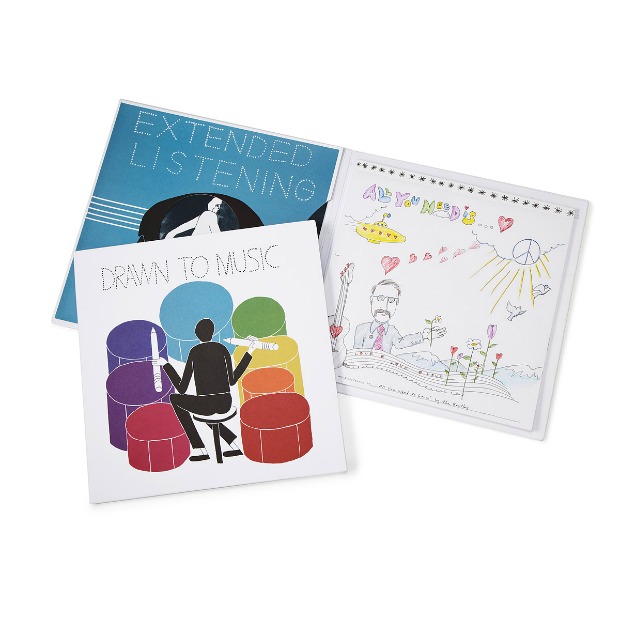

Drawn to Music | $20

There are as many as 2,000 varieties of cheese in the world—something for every taste, toasted cheese, and fondue pot. Just stroll into any cheese shop in Paris worth its fromage, and you’re likely to find scores—if not hundreds—of varieties of French cheese alone. But if you’re looking for something truly unique in the realm of fermented curd, you have to go to Bjurholm, Sweden to sample the moose cheese made by Älgen Hus. That’s right, Älgen Hus (“Elk House,” because moose are also known as elk there) is the world’s only producer of cheese made from moose milk. The unusual ingredient and sole source makes this Swedish cheese the world champion for rarity. Now, a polite warning to artisanal entrepreneurs who might be thinking of venturing into the Maine woods to milk a moose and make your own moose cheese: the three (yes, just three) milk-making cow moose at Älgen Hus—Gullan, Haelga, and Juna by name—are domesticated, whereas wild moose are formidable, 1,000 pound animals that definitely haven’t signed up for cheese-making.

Cardboard Animal Heads | $30 – 61

If you think hitting the snooze button is risky now, you would have been in some trouble during Industrial Revolution-era Britain and Ireland. Back then, alarm clocks were pricey and erratic, leaving workers with no way to guarantee making it to work on time. Enter the knocker-upper. While it may not be the most creatively named title, the job of the knocker-upper was to knock on your windows at a predetermined time until you woke up. The hired hands were mostly freelancers looking to earn some extra cash and they used long sticks of lightweight wood to reach upper floors. Once the 1920s hit, alarm clocks became more reliable and affordable and the job of a knocker-upper faded into obscurity. You could probably set your phone’s alarm to sound like a window bang though, if you could use some nostalgia with your morning.

Cube LED Alarm Clock | $32

For all humans reading this, the answer is yes! Human eyes can perceive more shades of green than any other color. But why green? Shouldn’t we be able to see all colors equally? On a purely scientific level, our vision gives green more weight because two out of the three types of cones in our retinas—medium and long cones—are most sensitive to the part of the spectrum of light that we perceive as green. Short cones favor the blue end of the spectrum, but the other two overlap in the middle, which is the sweet spot for all things green. But basic biology aside, is there a reason that our eyes evolved this way? There’s more interpretive debate here, but most scientists agree that it’s because we evolved in predominantly green environments like forests and jungles where, Darwin would argue, our ancestors who could perceive more shades of green were better equipped to distinguish the tastiest food sources. So, with this high-def color vision, human eyes are pretty sophisticated, huh? Enter the mighty mantis shrimp, which has twelve types of photoreceptors (versus humans’ three), which allow them to perceive a wider slice of the EM spectrum. Also, unlike mere humans, the peacock mantis shrimp can punch with the acceleration of a .22 caliber bullet. That’s 50 times faster than the blink of a human eye. It’s enough to make people green with envy…

Motherhood Tree of Life Custom Necklace | $125 – 155