The largest single-stemmed tree in the world is the giant sequoia, some grow up to 300 feet high or nearly 30 feet across. But growing even larger than that is a quaking aspen tree in Utah with a vast root system that has sprouted an entire grove of new trees. Known as Pando, the cluster of 40,000 tree trunks over a 106-acre area is actually a single organism. Some estimates date Pando’s age at 80,000 years, making it among the largest and oldest organisms on earth, but currently its survival is in peril. As Pando’s individual tree trunks die, they need to be replaced by new shoots springing up from its root system. Unfortunately, deer and other herbivores have developed a craving for aspen shoots, and they are on their way to grazing the ancient giant out of existence.

The largest single-stemmed tree in the world is the giant sequoia, some grow up to 300 feet high or nearly 30 feet across. But growing even larger than that is a quaking aspen tree in Utah with a vast root system that has sprouted an entire grove of new trees. Known as Pando, the cluster of 40,000 tree trunks over a 106-acre area is actually a single organism. Some estimates date Pando’s age at 80,000 years, making it among the largest and oldest organisms on earth, but currently its survival is in peril. As Pando’s individual tree trunks die, they need to be replaced by new shoots springing up from its root system. Unfortunately, deer and other herbivores have developed a craving for aspen shoots, and they are on their way to grazing the ancient giant out of existence.

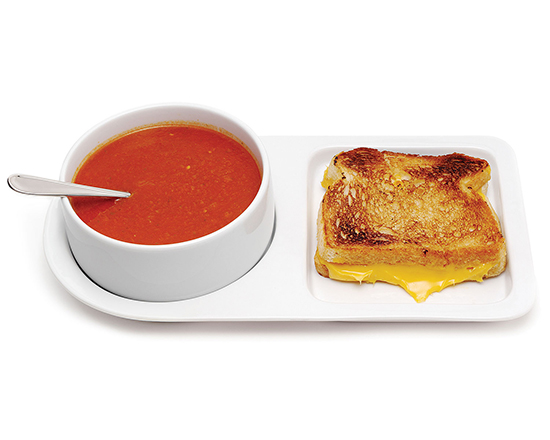

There are some foods that we think of as just naturally going together: cookies and milk, soup and sandwich, apples and cheese. The reasons for those pairings are as complex as the flavors themselves. Part of it just comes down to cultural preferences: should French fries be paired with ketchup, mayonnaise or gravy? The answer depends on what you grew up with. But flavor is ultimately about chemistry, and offers many variables to experiment with. When one food has a strong flavor, it diminishes your ability to taste that flavor as well in the food that it’s paired with. A piece of cake, for example, helps to moderate the sweetness of your dessert wine. Salt can help to reduce bitterness, which is why pretzels go so well with a mug of beer. At other times, one flavor can enhance another—vanilla is such an effective flavor enhancer that even chocolate doesn’t taste quite right without it. And food cultures all over the world favor the pairing of fats with astringent flavors (sharp, tangy, sour, etc.), whether that’s a dill pickle with your deli sandwich, wine with a fancy cheese assortment, or the zing of sliced ginger with your sushi.

There are some foods that we think of as just naturally going together: cookies and milk, soup and sandwich, apples and cheese. The reasons for those pairings are as complex as the flavors themselves. Part of it just comes down to cultural preferences: should French fries be paired with ketchup, mayonnaise or gravy? The answer depends on what you grew up with. But flavor is ultimately about chemistry, and offers many variables to experiment with. When one food has a strong flavor, it diminishes your ability to taste that flavor as well in the food that it’s paired with. A piece of cake, for example, helps to moderate the sweetness of your dessert wine. Salt can help to reduce bitterness, which is why pretzels go so well with a mug of beer. At other times, one flavor can enhance another—vanilla is such an effective flavor enhancer that even chocolate doesn’t taste quite right without it. And food cultures all over the world favor the pairing of fats with astringent flavors (sharp, tangy, sour, etc.), whether that’s a dill pickle with your deli sandwich, wine with a fancy cheese assortment, or the zing of sliced ginger with your sushi.

Sticks and stones may break your bones, but an embarrassing nickname can haunt you for centuries. King Alfonso IX of Leon, for example, is still recorded in the history books as “The Slobberer” because of his tendency to foam at the mouth when angry. Sometimes, however, the nicknames stick so well that we don’t even realize they are nicknames. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was given his nickname because he used the word “che” so often—it’s the Argentine equivalent of saying “dude” or “bro.” The ancient Greek philosopher Plato was actually named Aristocles. The name Plato was supposedly given to him by his wrestling coach, and means “broad”—perhaps the ancient Greek version of “tubby.” But when a nickname sticks, sometimes the best defense is to run with it. When James Hickock couldn’t shake the nickname “Duck Bill”—a reference to his large nose and protruding upper lip—he instead altered it just a bit, and became known as Wild Bill Hickok, one of the most famous gunslingers of the American West.

Sticks and stones may break your bones, but an embarrassing nickname can haunt you for centuries. King Alfonso IX of Leon, for example, is still recorded in the history books as “The Slobberer” because of his tendency to foam at the mouth when angry. Sometimes, however, the nicknames stick so well that we don’t even realize they are nicknames. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was given his nickname because he used the word “che” so often—it’s the Argentine equivalent of saying “dude” or “bro.” The ancient Greek philosopher Plato was actually named Aristocles. The name Plato was supposedly given to him by his wrestling coach, and means “broad”—perhaps the ancient Greek version of “tubby.” But when a nickname sticks, sometimes the best defense is to run with it. When James Hickock couldn’t shake the nickname “Duck Bill”—a reference to his large nose and protruding upper lip—he instead altered it just a bit, and became known as Wild Bill Hickok, one of the most famous gunslingers of the American West.

Well, that depends. Because parrots are one of several species (including humans) that give each individual a name to help distinguish them from the group. Researchers in Venezuela made careful observation of newborn parrot chicks to see how this naming process happens. What they found was not that the baby chick spontaneously creates its own name, but that the proud parent birds pick out names for their children. The birds carry those names throughout their life, although they may choose to alter them slightly—essentially giving themselves a nickname!

Well, that depends. Because parrots are one of several species (including humans) that give each individual a name to help distinguish them from the group. Researchers in Venezuela made careful observation of newborn parrot chicks to see how this naming process happens. What they found was not that the baby chick spontaneously creates its own name, but that the proud parent birds pick out names for their children. The birds carry those names throughout their life, although they may choose to alter them slightly—essentially giving themselves a nickname!

Called “snail” by the Italians and “monkey tail” by the Dutch, the asperand is now as much a part of our online lives as scrolling through newsfeed and untagging really unflattering pictures of ourselves from our last trip to the beach. However, the swirling symbol was pretty close to going extinct. First documented in 1536, the asperand was used by merchants to denote units, and was widely used in early commerce. The machine age was not friendly to our little symbol-that-could, though, and it was omitted from the first typewriters. It came back with a vengeance in 1971, when computer scientist Ray Tomlinson was trying to figure out a way to connect computer programmers. He needed a way to address a message from one computer to the next and it needed to include the user’s name, as well as the name of their computer, which could service many users. The symbol linking those two elements could not already be widely used in operating systems. He considered using the exclamation point, comma, and equal sign, but ironically, it was the @’s unpopularity that made it the ubiquitous symbol we all know today.

Called “snail” by the Italians and “monkey tail” by the Dutch, the asperand is now as much a part of our online lives as scrolling through newsfeed and untagging really unflattering pictures of ourselves from our last trip to the beach. However, the swirling symbol was pretty close to going extinct. First documented in 1536, the asperand was used by merchants to denote units, and was widely used in early commerce. The machine age was not friendly to our little symbol-that-could, though, and it was omitted from the first typewriters. It came back with a vengeance in 1971, when computer scientist Ray Tomlinson was trying to figure out a way to connect computer programmers. He needed a way to address a message from one computer to the next and it needed to include the user’s name, as well as the name of their computer, which could service many users. The symbol linking those two elements could not already be widely used in operating systems. He considered using the exclamation point, comma, and equal sign, but ironically, it was the @’s unpopularity that made it the ubiquitous symbol we all know today.

The words of the familiar New Year’s song “Auld Lang Syne” are actually an old Scottish poem. The poet Robert Burns submitted the words to the Scots Musical Museum in 1788, claiming it was a traditional verse and that he simply “took it down from an old man.” Historical evidence suggests, however, that while the first verse is adapted from a 1711 poem, the rest of the words were likely Burns’ own composition. The words “auld lang syne” literally mean “old long since.” It’s the equivalent of saying “long, long ago” or “days gone by,” and is even used in place of “once upon a time” in some Scottish stories.

The words of the familiar New Year’s song “Auld Lang Syne” are actually an old Scottish poem. The poet Robert Burns submitted the words to the Scots Musical Museum in 1788, claiming it was a traditional verse and that he simply “took it down from an old man.” Historical evidence suggests, however, that while the first verse is adapted from a 1711 poem, the rest of the words were likely Burns’ own composition. The words “auld lang syne” literally mean “old long since.” It’s the equivalent of saying “long, long ago” or “days gone by,” and is even used in place of “once upon a time” in some Scottish stories.

The New Year seems like a great time to start making change in your life. And yet, 25% of people keep setting the same goals, year after year, without ever achieving them. So what good are they? In 1979, there was a goal-setting study conducted among Harvard MBA students. Only 13% of them had made any specific goals for themselves, and only 3% of students had written those goals down. When a follow-up was conducted a decade later, it was found that the students with goals in mind were earning twice as much as their goal-less peers. Those who had written their goals down, however, were earning a whopping ten times more than the other 97% of their graduating class. So while writing down your desire to go to the gym or stop smoking may seem futile, it may in fact have amazing results.

The New Year seems like a great time to start making change in your life. And yet, 25% of people keep setting the same goals, year after year, without ever achieving them. So what good are they? In 1979, there was a goal-setting study conducted among Harvard MBA students. Only 13% of them had made any specific goals for themselves, and only 3% of students had written those goals down. When a follow-up was conducted a decade later, it was found that the students with goals in mind were earning twice as much as their goal-less peers. Those who had written their goals down, however, were earning a whopping ten times more than the other 97% of their graduating class. So while writing down your desire to go to the gym or stop smoking may seem futile, it may in fact have amazing results.

Virginia is possibly America’s most famous 8-year-old, although her fame is primarily due to a man whose name history has largely forgotten—Francis Pharcellus Church. Church had been a war reporter during the Civil War, and in 1897 he was an editor for The Sun, one of New York’s major newspapers. Young Virginia O’Hanlon had been told by her father that “if you see it in The Sun, it’s so.” So when her friends began to question the reality of Santa Claus, Virginia knew where to turn for an authoritative answer. Church’s response, which was titled Is There a Santa Claus? but is now better known by one of its key lines, was just a small article tucked low on the page, but it struck a chord with a war-weary populous looking for hope. It has gone on to become the most reprinted editorial of all time. Virginia herself went on to put her inquiring mind to good use, eventually earning her PhD from Fordham University and becoming a school administrator.

Virginia is possibly America’s most famous 8-year-old, although her fame is primarily due to a man whose name history has largely forgotten—Francis Pharcellus Church. Church had been a war reporter during the Civil War, and in 1897 he was an editor for The Sun, one of New York’s major newspapers. Young Virginia O’Hanlon had been told by her father that “if you see it in The Sun, it’s so.” So when her friends began to question the reality of Santa Claus, Virginia knew where to turn for an authoritative answer. Church’s response, which was titled Is There a Santa Claus? but is now better known by one of its key lines, was just a small article tucked low on the page, but it struck a chord with a war-weary populous looking for hope. It has gone on to become the most reprinted editorial of all time. Virginia herself went on to put her inquiring mind to good use, eventually earning her PhD from Fordham University and becoming a school administrator.