It’s a sweetly eccentric holiday tradition: on Christmas morning the children rush to the Christmas tree, trying to spot a glass ornament shaped like a pickle. The lucky child who does so first is blessed with a year of good luck, or perhaps even an extra present. In America, the tradition first appeared during the 1890s when beautiful, glass Christmas ornaments began to be important from Germany. It was said that the holiday cuke was an old German custom, known as the Weihnachtsgurke. However, there is no historic evidence of such a tradition actually being practiced overseas. It appears that, instead, the Christmas pickle was part of a great American tradition: marketing. The story of the pickle’s German origins was most likely made up at that time to help sell more of the unusual ornaments, but the century of fun that it has inspired is completely authentic.

It’s a sweetly eccentric holiday tradition: on Christmas morning the children rush to the Christmas tree, trying to spot a glass ornament shaped like a pickle. The lucky child who does so first is blessed with a year of good luck, or perhaps even an extra present. In America, the tradition first appeared during the 1890s when beautiful, glass Christmas ornaments began to be important from Germany. It was said that the holiday cuke was an old German custom, known as the Weihnachtsgurke. However, there is no historic evidence of such a tradition actually being practiced overseas. It appears that, instead, the Christmas pickle was part of a great American tradition: marketing. The story of the pickle’s German origins was most likely made up at that time to help sell more of the unusual ornaments, but the century of fun that it has inspired is completely authentic.

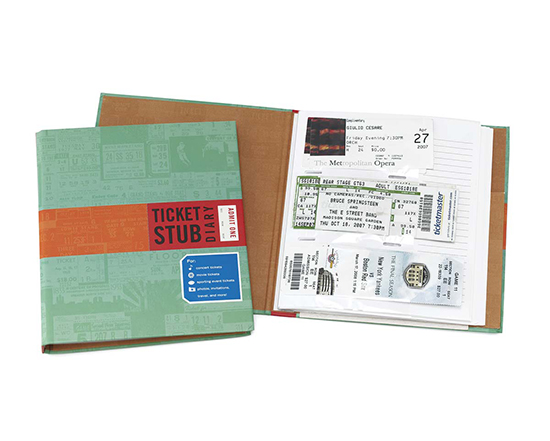

A claqueur is a professional applauder. That’s right. They earned a living by attending operas, plays and ballets and clapping loudly. The position has appeared throughout history in some form wherever there were people whose large egos needed massaging, but it began to be formalized into an actual career in France during the Renaissance. By the 1800s, there were even professional organizations for them, and specialized skills: there were those hired to weep at tragedies, others who would laugh infectiously during comedies, and some guaranteed to cry out for encores. They could even extort money from popular performers with the threat of booing during their bows. So, who needs a claqueur today? Everyone! Imagine how much better life would be with someone guaranteed to find your jokes hilarious and your stories fascinating.

A claqueur is a professional applauder. That’s right. They earned a living by attending operas, plays and ballets and clapping loudly. The position has appeared throughout history in some form wherever there were people whose large egos needed massaging, but it began to be formalized into an actual career in France during the Renaissance. By the 1800s, there were even professional organizations for them, and specialized skills: there were those hired to weep at tragedies, others who would laugh infectiously during comedies, and some guaranteed to cry out for encores. They could even extort money from popular performers with the threat of booing during their bows. So, who needs a claqueur today? Everyone! Imagine how much better life would be with someone guaranteed to find your jokes hilarious and your stories fascinating.

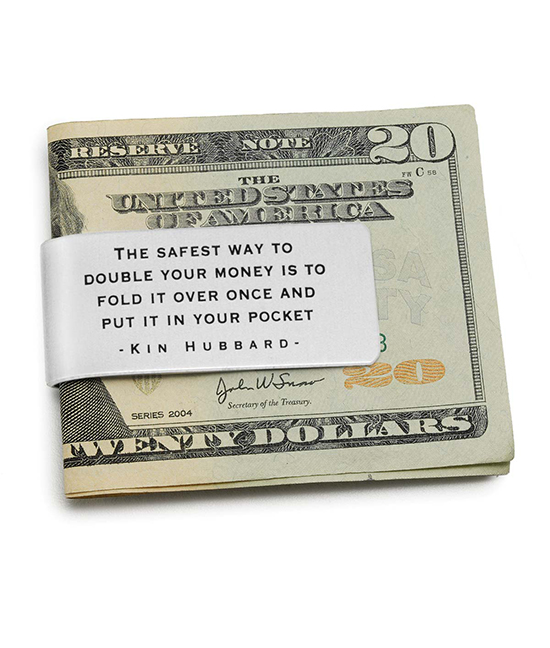

None. Zero. Nada. Not a single tree is cut down to make the great American greenback. It’s not because the government has instituted an environmentally responsible recycling program, but rather because the paper used for currency is completely unlike the stuff we use for printing and writing. Wood pulp-based paper is designed to be affordable and mass produced, but is not necessarily very durable. Paper money, on the other hand, needs to be able to survive years of wallets, pockets and vending machines. It also needs to be difficult to reproduce, as a way of deterring forgery. So those bills in your pocket are actually more like fabric, made from a unique, legally-protected blend of cotton and linen fiber.

None. Zero. Nada. Not a single tree is cut down to make the great American greenback. It’s not because the government has instituted an environmentally responsible recycling program, but rather because the paper used for currency is completely unlike the stuff we use for printing and writing. Wood pulp-based paper is designed to be affordable and mass produced, but is not necessarily very durable. Paper money, on the other hand, needs to be able to survive years of wallets, pockets and vending machines. It also needs to be difficult to reproduce, as a way of deterring forgery. So those bills in your pocket are actually more like fabric, made from a unique, legally-protected blend of cotton and linen fiber.

While no dinosaur is exactly dime-a-dozen these days, one might argue that the hardest to find is the Archaeopteryx. And not just any old proto-bird, but specifically the one known as the “Maxberg specimen.” It was dug from a German quarry in 1956. Eduard Opitsch, the quarry owner, allowed the Maxberg Museum to display the specimen while he sought a buyer for his find. But, although he received bids from various museums, in the end he simply decided to keep it himself. He took the fossil home, and it was never seen again. When Opitsch passed away in 1991, his home and records were examined with no luck—the Archaeopteryx had flown the coop for good.

While no dinosaur is exactly dime-a-dozen these days, one might argue that the hardest to find is the Archaeopteryx. And not just any old proto-bird, but specifically the one known as the “Maxberg specimen.” It was dug from a German quarry in 1956. Eduard Opitsch, the quarry owner, allowed the Maxberg Museum to display the specimen while he sought a buyer for his find. But, although he received bids from various museums, in the end he simply decided to keep it himself. He took the fossil home, and it was never seen again. When Opitsch passed away in 1991, his home and records were examined with no luck—the Archaeopteryx had flown the coop for good.

In 1877, a young man named Arthur Conan Doyle became a clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. One of his duties was to conduct intake interviews for new patients of pathologist Dr. Joseph Bell—who had a gift for deducing much of the same information simply by observing the details of a person’s dress and behavior. He was legendary for predicting a person’s birthplace, habits, recent actions and more without a word of explanation from the person. And while Dr. Bell was not Sherlock Holmes to the letter, he was periodically called in by the police to consult on criminal investigations, including the Jack the Ripper murders. Sometimes, however, life can also imitate fiction. In 1890—three years after Sherlock Holmes first appeared in prints—Dr. Bell went to assist on a particularly scandalous murder of a student by his tutor. Helping Dr. Bell was a ballistics expert who just happened to be named Dr. Watson.

In 1877, a young man named Arthur Conan Doyle became a clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. One of his duties was to conduct intake interviews for new patients of pathologist Dr. Joseph Bell—who had a gift for deducing much of the same information simply by observing the details of a person’s dress and behavior. He was legendary for predicting a person’s birthplace, habits, recent actions and more without a word of explanation from the person. And while Dr. Bell was not Sherlock Holmes to the letter, he was periodically called in by the police to consult on criminal investigations, including the Jack the Ripper murders. Sometimes, however, life can also imitate fiction. In 1890—three years after Sherlock Holmes first appeared in prints—Dr. Bell went to assist on a particularly scandalous murder of a student by his tutor. Helping Dr. Bell was a ballistics expert who just happened to be named Dr. Watson.

While this tabletop rule has been drilled into your head since you graduated from your high chair, its supposed origins suggest it’s more need-based than the pinnacle of politeness. During medieval times, everyone and their barber would be invited to elaborate dinners at long, crowded tables. With surface space at a premium, no elbow could be placed on the table without landing in someone else’s territory—or in their food! But seeing as how we now enjoy more spacious dining accommodations, have at it! Modern rules dictate that elbows are free game once you’ve put down your utensils.

While this tabletop rule has been drilled into your head since you graduated from your high chair, its supposed origins suggest it’s more need-based than the pinnacle of politeness. During medieval times, everyone and their barber would be invited to elaborate dinners at long, crowded tables. With surface space at a premium, no elbow could be placed on the table without landing in someone else’s territory—or in their food! But seeing as how we now enjoy more spacious dining accommodations, have at it! Modern rules dictate that elbows are free game once you’ve put down your utensils.

Back in your school English classes, your teacher instructed you in the wonders of figurative language. Metaphor and simile, for example. Or, if your teacher was more ambitious, such devices as sibilance and synecdoche. But there is a whole realm of language mechanics that even the bravest high school educator will not breach. Anastrophe, for example, is when a grammatically correct sentence has its pieces rearranged. Think Yoda from Star Wars: “Patience you must have.” Antimetabole is the use of the same words in successive clauses, but in reverse order: “Do what you like, and like what you do.” Epanalepsis creates emphasis by using the same word or phrase at both the beginning and end of a sentence: “The king is dead; long live the king!” Merism refers to a single thing by referring to its parts: you use this figure of speech whenever you address “Ladies and gentlemen!” when referring to an audience. Tmesis allows you to chop a single word in half, so that you can insert a different word into its middle for emphasis: “Abso-bloomin’-lutely!” And zeugma gets complicated, by having two different parts of a sentence tie into a single word or phrase: Dickens wrote how a broken-hearted young lady “went straight home, in a flood of tears and a sedan-chair.”

Back in your school English classes, your teacher instructed you in the wonders of figurative language. Metaphor and simile, for example. Or, if your teacher was more ambitious, such devices as sibilance and synecdoche. But there is a whole realm of language mechanics that even the bravest high school educator will not breach. Anastrophe, for example, is when a grammatically correct sentence has its pieces rearranged. Think Yoda from Star Wars: “Patience you must have.” Antimetabole is the use of the same words in successive clauses, but in reverse order: “Do what you like, and like what you do.” Epanalepsis creates emphasis by using the same word or phrase at both the beginning and end of a sentence: “The king is dead; long live the king!” Merism refers to a single thing by referring to its parts: you use this figure of speech whenever you address “Ladies and gentlemen!” when referring to an audience. Tmesis allows you to chop a single word in half, so that you can insert a different word into its middle for emphasis: “Abso-bloomin’-lutely!” And zeugma gets complicated, by having two different parts of a sentence tie into a single word or phrase: Dickens wrote how a broken-hearted young lady “went straight home, in a flood of tears and a sedan-chair.”

The history of French toast, like the food itself, is rich but not very transparent. Similar recipes date all the way back to ancient Greece. There is written record of the food in medieval England, but with a French name: pain perdu. That title, which means “lost bread” in reference to how battering could make a stale loaf palatable, is still used in America’s Cajun country. When the term specific phrase “French toast” first appeared in the 1660s, it was referring to a cooked bread that had been soaked in wine and fruit juice, rather than an egg dip. And when the dish as we know it now started to grow in popularity in 19th century America, it was just as likely to be known as “German toast,” “Spanish toast,” or simply “egg toast.” It is generally agreed, however, that the all-American version of the food—a New York innkeeper named Joseph French invented the recipe in 1724 and named it after himself—is unlikely to be true.

The history of French toast, like the food itself, is rich but not very transparent. Similar recipes date all the way back to ancient Greece. There is written record of the food in medieval England, but with a French name: pain perdu. That title, which means “lost bread” in reference to how battering could make a stale loaf palatable, is still used in America’s Cajun country. When the term specific phrase “French toast” first appeared in the 1660s, it was referring to a cooked bread that had been soaked in wine and fruit juice, rather than an egg dip. And when the dish as we know it now started to grow in popularity in 19th century America, it was just as likely to be known as “German toast,” “Spanish toast,” or simply “egg toast.” It is generally agreed, however, that the all-American version of the food—a New York innkeeper named Joseph French invented the recipe in 1724 and named it after himself—is unlikely to be true.