There may be a lot of qualities that go into being a great mother, but if you’re speaking numerically, the greatest mother ever was an 18th century Russian peasant woman. Hailing from the hamlet of Shuya, it’s believed that her name was Valentina, although on official records she was always referred to as Mrs. Feodor Vassilyev. Over a 40-year period, Mrs. Vassilyev gave birth 27 times. Impressive, you say? That’s not all. Of those 27 births, 16 were pairs of twins, 7 were triplets, and 4 were quadruplets. That adds up to a grand total of 69 children, and what must have been some pretty intense Mother’s Day celebrations.

There may be a lot of qualities that go into being a great mother, but if you’re speaking numerically, the greatest mother ever was an 18th century Russian peasant woman. Hailing from the hamlet of Shuya, it’s believed that her name was Valentina, although on official records she was always referred to as Mrs. Feodor Vassilyev. Over a 40-year period, Mrs. Vassilyev gave birth 27 times. Impressive, you say? That’s not all. Of those 27 births, 16 were pairs of twins, 7 were triplets, and 4 were quadruplets. That adds up to a grand total of 69 children, and what must have been some pretty intense Mother’s Day celebrations.

Anna Jarvis is perhaps the only person in history who would go to great lengths to discredit Mother’s Day cards. Jarvis believed that Mother’s Day should be spent in prayerful reflection and sincere gratitude for our mothers, not as the commercialized shopping opportunity it had become by the 1920s. To her, a gift of chocolate was an empty gesture, and a purchased card “means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world.” Jarvis campaigned fiercely for her cause, forming the Mother’s Day International Association and even trademarking the phrase “Mother’s Day”. She met with little public support, and was even once arrested for disturbing the peace. Why was Jarvis so worked up about Mother’s Day? Because she was the woman who lobbied to make it a national holiday in the first place.

Anna Jarvis is perhaps the only person in history who would go to great lengths to discredit Mother’s Day cards. Jarvis believed that Mother’s Day should be spent in prayerful reflection and sincere gratitude for our mothers, not as the commercialized shopping opportunity it had become by the 1920s. To her, a gift of chocolate was an empty gesture, and a purchased card “means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world.” Jarvis campaigned fiercely for her cause, forming the Mother’s Day International Association and even trademarking the phrase “Mother’s Day”. She met with little public support, and was even once arrested for disturbing the peace. Why was Jarvis so worked up about Mother’s Day? Because she was the woman who lobbied to make it a national holiday in the first place.

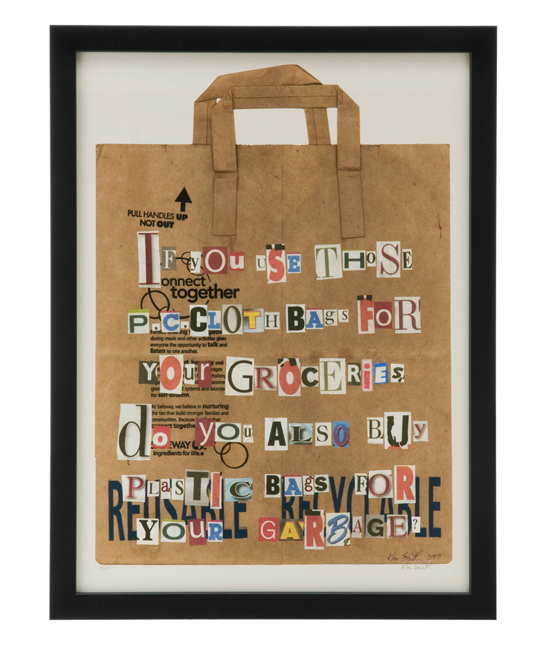

Your mom may have packed up your lunch-break PB&J, but she couldn’t have done it without the help of Margaret Knight. Living in 19th century America, Knight was something we don’t often hear about in that age: a prolific woman inventor. She designed a kind of window sash, a numbering machine, and even a form of internal combustion engine. When an ironsmith she had hired to build a prototype for one invention tried to steal her patent, she wasn’t afraid to take him to court and reclaim her intellectual property. But Knight’s most lasting innovation can still be seen in grocery stores and school cafeterias. She invented a machine that folded and glued flat-bottomed, brown paper bags.

Your mom may have packed up your lunch-break PB&J, but she couldn’t have done it without the help of Margaret Knight. Living in 19th century America, Knight was something we don’t often hear about in that age: a prolific woman inventor. She designed a kind of window sash, a numbering machine, and even a form of internal combustion engine. When an ironsmith she had hired to build a prototype for one invention tried to steal her patent, she wasn’t afraid to take him to court and reclaim her intellectual property. But Knight’s most lasting innovation can still be seen in grocery stores and school cafeterias. She invented a machine that folded and glued flat-bottomed, brown paper bags.

Yes and no. The kind of DNA that we typically think of in our cells, which is responsible for giving you your father’s nose or your mother’s dimples, definitely comes from both parents. However, that’s not the only kind of DNA you have. Inside your cells are a variety of “organelles” that perform specific functions. One of those, the mitochondrion, is known as the cell’s power plant. It also happens to contain its own independent set of DNA. Research suggests that this genetic material actually has a separate evolutionary origin than our regular DNA, and that mitochondria may have once been bacteria that established a symbiotic relationship within our cells. The other surprising fact about mitochondrial DNA? Children only inherit it from their mothers.

Yes and no. The kind of DNA that we typically think of in our cells, which is responsible for giving you your father’s nose or your mother’s dimples, definitely comes from both parents. However, that’s not the only kind of DNA you have. Inside your cells are a variety of “organelles” that perform specific functions. One of those, the mitochondrion, is known as the cell’s power plant. It also happens to contain its own independent set of DNA. Research suggests that this genetic material actually has a separate evolutionary origin than our regular DNA, and that mitochondria may have once been bacteria that established a symbiotic relationship within our cells. The other surprising fact about mitochondrial DNA? Children only inherit it from their mothers.

Thanks, Mom!

Actually, recycling looks very good on paper. According to the EPA, every year Americans consume 71 million tons of paper and paper packaging, but more than 60% of that is being recycled. Recycled paper fiber is such an efficient way of making paper that it requires only 60% as much energy, let alone other resources. For every ton of recycled paper produced, 17 trees, 7,000 gallons of water and 380 gallons of oil are saved—along with enough electricity to power an American family for six months!

Actually, recycling looks very good on paper. According to the EPA, every year Americans consume 71 million tons of paper and paper packaging, but more than 60% of that is being recycled. Recycled paper fiber is such an efficient way of making paper that it requires only 60% as much energy, let alone other resources. For every ton of recycled paper produced, 17 trees, 7,000 gallons of water and 380 gallons of oil are saved—along with enough electricity to power an American family for six months!

If your umbrella is old enough, maybe it really did grow feet and walk away. In Japanese folklore, when an inanimate object has been used for 100 years, it comes to life and transforms into a kind of spirit creature called a “tsukumogami.” In the modern world of disposable goods, it’s hard to imagine using a household item for so long, but it must have been not uncommon in 10th century Japan, because the list of known tsukumogami is pretty extensive. In fact, the sub-species of sentient umbrellas were common enough that they had their own name: kasa-obake. They are said to hop around on their single foot, glaring mischievously through their one eye, sometimes with a long tongue hanging from their mouth. So be sure to treat your umbrella well—you really want to stay on its good side.

If your umbrella is old enough, maybe it really did grow feet and walk away. In Japanese folklore, when an inanimate object has been used for 100 years, it comes to life and transforms into a kind of spirit creature called a “tsukumogami.” In the modern world of disposable goods, it’s hard to imagine using a household item for so long, but it must have been not uncommon in 10th century Japan, because the list of known tsukumogami is pretty extensive. In fact, the sub-species of sentient umbrellas were common enough that they had their own name: kasa-obake. They are said to hop around on their single foot, glaring mischievously through their one eye, sometimes with a long tongue hanging from their mouth. So be sure to treat your umbrella well—you really want to stay on its good side.

Technically, yes. Unlike a substance like water that changes from a liquid to a solid when frozen, glass develops no crystalline structure to maintain a rigid structure. For decades, science textbooks have supported this fact by pointing to the windows of medieval churches. Those window panes are often thicker at the bottom, and popular wisdom was that they had “flowed” downward at a very slow rate. In the late 1990s, however, some scientists decided to actually test that theory. They confirmed that, yes, glass would in fact exhibit some flow over time, but that it would take at least 10 million years for any visible change to occur in those window panes. It turns out that the sagging medieval glass, from mere hundreds of years ago, is only evidence of the period’s primitive glassmaking techniques.

Technically, yes. Unlike a substance like water that changes from a liquid to a solid when frozen, glass develops no crystalline structure to maintain a rigid structure. For decades, science textbooks have supported this fact by pointing to the windows of medieval churches. Those window panes are often thicker at the bottom, and popular wisdom was that they had “flowed” downward at a very slow rate. In the late 1990s, however, some scientists decided to actually test that theory. They confirmed that, yes, glass would in fact exhibit some flow over time, but that it would take at least 10 million years for any visible change to occur in those window panes. It turns out that the sagging medieval glass, from mere hundreds of years ago, is only evidence of the period’s primitive glassmaking techniques.

There’s a man in the moon because you put him there. Specifically, part of your brain put him there. Dr. Doris Tsao, a neuroscientist from Germany, was doing research on stroke victims and discovered that some patients were able to recognize and identify any object except for faces. This suggested to her that facial recognition may occur in a very specific part of the brain. Testing showed her theory to be true, and further research has created a list of twelve visual attributes that cause these facial-related parts of the brain to activate. The hitch is that, if any object exhibits enough of these characteristics, our brains automatically identify a face even where none actually exists. Thus, we tend to see faces staring back at us from electrical outlets, grilled cheese sandwiches, or even the craters of the moon.

There’s a man in the moon because you put him there. Specifically, part of your brain put him there. Dr. Doris Tsao, a neuroscientist from Germany, was doing research on stroke victims and discovered that some patients were able to recognize and identify any object except for faces. This suggested to her that facial recognition may occur in a very specific part of the brain. Testing showed her theory to be true, and further research has created a list of twelve visual attributes that cause these facial-related parts of the brain to activate. The hitch is that, if any object exhibits enough of these characteristics, our brains automatically identify a face even where none actually exists. Thus, we tend to see faces staring back at us from electrical outlets, grilled cheese sandwiches, or even the craters of the moon.